April 29, 2006 Article Latest Between The Lines Article Between The Lines Archives:

Tennis Server

|

|

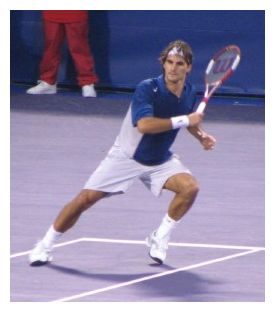

Not since Rod Laver in 1969 has a male player captured all four Slam tournaments in a single calendar year, the classic Grand Slam. Indeed, no-one has won the first two Slams in a given year--Australia and Roland Garros--since Jim Courier did so in 1992. But this year, 2006, there seems a plausible chance that these rare achievements could indeed happen. The man that could break through is of course Roger Federer, who has already captured the year's first Slam, Australian Open 06. Roger brings superior credentials to the quest including seven career Slam triumphs to date. At age 24 his tennis is probably at its career peak or nearly so. His recent triumphs on hard courts at Indian Wells and Miami strengthen his place as favorite to repeat as champion at both Wimbledon and U.S. Open later this year. Thus Roger's most difficult barrier enroute to his possible Grand Slam appears to lie just ahead -- at Roland Garros, the only Slam played on clay and the only Slam that Federer has not yet conquered. ROGER AS CLAY ARTIST Five different players have won Roland Garros in our current century, none more than once. All five champions have come from either Spain or South America, and four of the five runners-up have also been from the same regions. All dislike being called clay-court specialists, as all are also attractive competitors on hard courts. Still, none have them has won a Slam other than at Garros, and Gaston Gaudio, for example, Garros champion in 2004, shows a lifetime record at the other Slams of only 12-19. Meanwhile the recent champions of the grass-court and hard-court Slams have come from other parts of the world. Their primary strengths have been generally in their in powerful serves, attacking ground-strokes, and, especially in earlier decades, skills at net.

Roger's fast-court abilities, including superb net play, soared in his Wimbledon triumph of 2003. Since then in winning six more Slams--two more Wimbledons, two U.S. Opens, and two Australians--he has shown a wonderfully balanced game of both power and finesse, finished in all areas. Most remarkably, he has shown an unusual ability to produce his very best tennis when it counted most--i.e., late in important matches late in tournaments. Opponents in early rounds sometimes win sets, where Roger typically plays a quiet tennis, well within his capabilities.. But whenever matters became climactic, Roger always seems able to step up the pace and pressure, employing as main weapon the penetrating velocity and fierce topspin of his attacking forehand. The result has been an almost-perfect W-L record in the final rounds of tournaments. In short, Roger has become world's champion by producing relentless attack when needed. But clay is a surface that helps the defense not the offense. The attacking player's best thrusts lose energy on the clay-court bounce and tend to pay off less immediately. As points become extended, the attacker's winners can become outnumbered by his errors. But if Roger is the game's supreme attacker, he is also excellent defensively, and he is entirely comfortable against most opponents amid neutral play. He patiently exchanges corner-to-corner backhands, mixing overspin and slice, varying pace and placement amid superb court movement. Meanwhile he brings the speed and stroking ability of a top counter-puncher--able to reach opponent's volleys and angled shots early enough to nail the exposed openings. His serve, like everyone's, loses forward energy on the clay-court bounce, but his command of spin, variety, and control in serving are inestimably useful on clay. Finally, he is excellent, perhaps superior, in the close-in cat-and-mouse game. Roger's appearances on clay are only moderately frequent. But he has competed at Garros in every year starting in 1999. He reached the quarters in 2001 but his best showing came last year, when he reached the semis before losing in four sets to the eventual champion, Rafael Nadal. All five of his match victories were achieved in three straight sets, and his victims included several hard-hitting clay artists. He has also competed regularly in the German Open, held in Hamburg on red clay two weeks before Garros. Roger triumphed there in 2002, 2004, and 2005. In winning all six of his matches there last year, he revenged an earlier clay-court loss to Gasquet and also defeated top-level clay warriors Davydenko, Coria, and Robredo. Roger has also sometimes entered Monte Carlo or Rome, and he reached the final at Rome in 2003 and at Monte Carlo in 2006 (to be discussed below). The Swiss national open is played on clay, at Gstaad, and Roger won it in 2004. Meanwhile his Davis Cup record on clay courts has been excellent. Thus the nature and quality of his weaponry and his past record on clay verify that Roger is a superb clay-courter. Indeed, anyone who has won Hamburg three times in four years before reaching age 24 is no clay neophyte. Federer is probably the world's second-best clay-court player today. But the world's best player on clay is Rafael Nadal, Roger's current nemesis. The highly charged Spanish teen-ager won his last 36 clay-court matches in 2005 and has added to the string with every win so far in 2006. Rafael and Roger have played each other two times on clay. Both meetings became immediate classics, high in quality and intensity. Together they provide intriguing perspective toward a possible, indeed probable, meeting at Garros 06. GARROS 2005 -- NADAL d. FEDERER 63 46 64 63 Stadium Chatrier was filled for the semi-final show-down, pitting Rafael Nadal, the upstart recent winner at Monte Carlo and Rome, against the current world champion and recent winner at Hamburg. The day was cool, damp, windy--conditions scarcely favorable for Roger Federer's attacking style. Roger started poorly, losing the first game and eventually the first set amid far too many errors. At net, Roger's success rate was dismal. An intruding shower promised even slower conditions to come--i.e., more trouble for Roger. But upon resumption, Roger improved his consistency and raised his forcing play, often drawing returns from Rafael that were attackable. Roger's favorite sequence--serve, forcing approach, then volley, all delivered with punch--were too strong even for Rafael's superb counter-punching skills. When returning serve, Federer regularly stepped inside baseline to paste Rafael's offering to a far corner. Although Roger was generally the attacker, many points followed other patterns. There were countless neutral exchanges, and Roger also was more than occasionally on the defensive. Meanwhile every rocket to a corner and every sortie forward by Roger was chancy in the face of Rafael's speed afoot, power, and accuracy. At four-games-all in the third set Rafael raised his pace and overspin in stroking, and the teen-ager finally won the set with a fine swinging volley in forecourt. Federer's errors had been increasing, especially off his forehand, and his first-serve percentage was badly in decline. It was Nadal ahead, two sets to one. Roger captured an early service break in set four. Most points were well contested, and most games were drawn-out amid fading twilight. The unraveling began in game six, Roger serving, when the Swiss star missed two set-up forehands from inside baseline. Roger's distemper with the conditions and his own mistakes now grew. Rafael pulled ahead in game eight helped by a close Federer error and a heavily overspun mortar by Rafael that just clipped the baseline. Rafael now needed only to hold serve, and he produced three outright winners to the corners in doing so. It had been a memorable affair, settled by narrow margin. Rafael afterwards went on to defeat Puerta in the final and thereby capture Garros in his first try. It was a remarkable achievement for so young a player, honored in the decision to honor Rafael as Tennis Server's Player of the Year for 2005. The high-energy Mallorcan was, however, sidelined for several months late in the year with a persistent foot injury. Federer meanwhile captured Wimbledon 05, U.S. Open 05, and Australia 06. MONTE CARLO 06 -- NADAL d. FEDERER 62 67 63 76 The two men next met on a hard court in Dubai in early 2006, Nadal winning two of three sets. Both then returned to the clay wars in mid-April 2006 at Monte Carlo. Both advanced to their final-round meeting by winning five matches with loss of only one set. It was another wondrous affair--well played, intensely contested. I did not watch the match, but my colleage, Pablo Sanfrancisco, whose photography has appeared often on Tennis Server, viewed and re-viewed substantial segments on tape. Pablo grew up and learned his early tennis in Spain prior to attending college in America. Pablo warmly admired the quality and evenness of the play. Nadal habitually roamed his comfort area 5-10 feet behind the baseline, using his speed afoot to maintain rallies and using the clay surface to reduce the sting from Roger's fire. Rafael's heavy, overspin ground-strokes from deep court made it difficult for Roger to attack. Pablo especially noted Rafael's quickness at moving forward to produce firm, angled deliveries designed to move Roger well away from optimum position. To Pablo, Rafael seemed at least equal to Roger in his ability to punish balls that were only moderately short and then to advance and exploit net position. Federer, in contrast, operated generally up close to baseline, even more intent to attack any vulnerable offering by his opponent. Roger started the match poorly, however--in trouble throughout the first set under Rafael's consistency and firm hitting, but Roger recovered to reach and capture a second-set tiebreaker. Rafael then seemed to gain in command, winning set three and moving ahead by two service breaks in set four. Roger battled back to reach six games all and took the early lead in the tiebreaker, but the world Number One then faltered in making several close errors on forcing attempts. Closing in on victory, Rafael raised his play beyond even his general high level. To Pablo's admiration, it ended with Rafael first moving Roger to the backhand corner, then executing a high-risk down-the-line drive to the same corner, wrong-footing Roger for the concluding winner. PRESCRIPTIONS Afterwards, Roger was quoted saying that he was gradually learning how to play against Rafael. We must guess at his full meaning, but several things seem obvious. Roger of course must maintain his confidence against Rafael, and his words, just noted, are probably part of his doing so. He must not allow fear of losing to sap his ability to find and sustain his very best tennis. Second, it seems obvious that if Roger is to defeat Rafael, whether on clay or hard, it must be with his attacking game. Perhaps Roger, who lost the first set to Rafael in four of their five of their matches to date, should move away from his penchant for working his way into matches gradually. Thus he should resolve to unleash his attack earlier in matches, and--probably more important--he must not wait too long during points to start weighing in his wonderful power forehand. Roger knows that his rocketry will not yield from Rafael the immediate openings it sometimes creates. But the heavy barrage, once begun, must be sustained with high resolve and, of course, without error. To retreat to neutrality is to sacrifice the boldness and risks already invested in the point. Corollary tactics follow--occasional drop shots and short angles mainly to keep Rafael a little shorter in court than he prefers, attacks against Rafael's serves by stepping in to find better angles, lots of variety in serving. I greatly admire Roger's success to date often without on-site help by a professional coach. But the problem presented by Rafael may require of Roger a level of mental strength that comes from having a close and demanding mentor who holds Roger's confidence. Rafael's formula, of course, has already proven successful against Roger, having prevailed in four of their five past meetings including two of three on hard courts. Rafael is surely thirsty to extend his success, and his willingness--indeed eagerness--last year to compete on Wimbledon grass is absolutely exemplary. Rafael has the advantage of being nearly five years the younger, though his foot problem at young age is slightly troubling. He has probably learned not to waste energy on meaningless displays between points and during changeovers. As to their chances in their next meeting, I rate the two men just about equal. Roger is a slight favorite in calculations predicting outcomes at Garros 06, though the results of the forthcoming Italian and German Opens will greatly affect the final computer prediction. (The current calculations rank the tier just below the two leaders as follows: Coria, Nalbandian, Ferrer, Gaudio, Davydenko, Ljubicic.) Whether or not Roger keeps his Grand Slam chances alive this year, we can be sure that many historic meetings between the two lie ahead. I thank Pablo for his perceptive comments, sketched above.

--Ray Bowers

1995 - May 1998 | August 1998 - 2003 | 2004 - 2015

This column is copyrighted by Ray Bowers, all rights reserved.

Following interesting military and civilian careers, Ray became a regular

competitor in the senior divisions, reaching official rank of #1 in the 75

singles in the Mid-Atlantic Section for 2002. He was boys' tennis coach for four

years at Thomas Jefferson High School for Science and Technology, Virginia, where

the team three times reached the state Final Four. He was named Washington

Post All-Metropolitan Coach of the Year in 2003. He is now researching a history

of the early pro tennis wars, working mainly at U.S. Library of Congress. A

tentative chapter, which appeared on Tennis Server, won a second-place award

from U.S. Tennis Writers Association.

Questions and comments about these columns can be directed to Ray by using this form.

|

October 2022 Tennis Anyone: Patterns in Doubles by John Mills. September 2022 Tennis Anyone: Short Court by John Mills. |

You will join 13,000 other subscribers in receiving news of updates to the Tennis Server along with monthly tennis tips from tennis pro Tom Veneziano.

You will join 13,000 other subscribers in receiving news of updates to the Tennis Server along with monthly tennis tips from tennis pro Tom Veneziano.