January 10, 2010 Article Latest Between The Lines Article Between The Lines Archives:

Tennis Server

|

|

by Ray Bowers

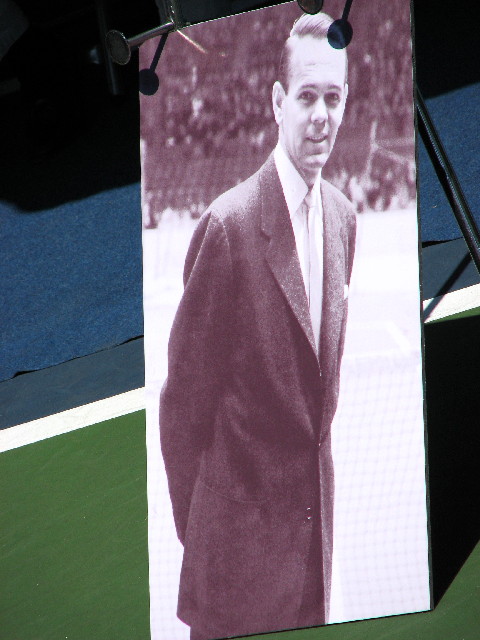

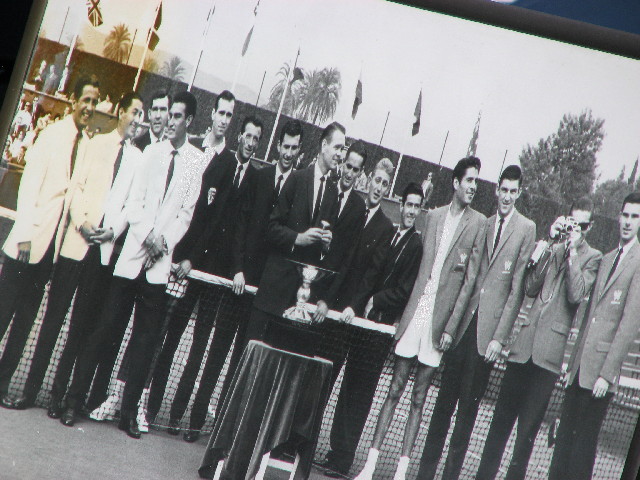

"If you don't come in on your second serve, your opponent will."The competitive and ever-dramatic modern sport-business of international tennis arose from the several decades of sometimes stormy transition that followed the Second World War. Central amid the controversies of that formative period was this tall product of the American West -- a six-footer who was world champion of tennis as player and then for many years its most influential mover on the business side. A pioneer both in how the game was played and then in shaping its marriage to the making of money, Jack Kramer stands as tennis's monumental representative of his times. John Albert Kramer was born in Las Vegas in 1921 and died at age 88 on September 12, 2009, at his Los Angeles home. Soon after his death, many of the sport's leading persons, including Tennis Server's publisher Cliff Kurtzman, came together in L. A. to honor his contributions and greatness (see photos below). SUPERSTAR Kramer's tennis development started at age 12 in southern California, favored by the excellent opportunities there for coaching and competition. At age 13, Jackie lost in the first round at Santa Monica in a field that included "little Bobby Riggs, little Joe Hunt, little Ted Schroeder" -- all future U.S. Nationals champions like Jack himself and all three significant figures in this account. Jack took lessons from tough pro Dick Skeen and was helped by Perry Jones at L. A. Tennis Club. He rapidly moved to the top of the California age-group rankings and, guided by a local student of the game, Cliff Roche, developed a net-attacking style blended with careful adherence to percentage play. From Roche, Jack early learned the importance of the second serve -- how to attack that of his opponent and protect his own. Kramer at age 18 became a surprise member of the U.S. Davis Cup team in 1939. In the final round against the Australians outside Philadelphia, Americans Riggs and Parker won both first-day's singles matches. On the second day, Kramer with Joe Hunt, who was only two years older than Jack, faced Bromwich-Quist, who had recently won the U.S. Nationals doubles tournament. The power serving of Hunt and the overhead game of Kramer gave the young Californians the first set, but the excellence of the Aussies in commanding net produced an ultimately convincing four-set victory. Hunt-Kramer led in aces and placements, but yielded nearly double the errors of their opponents. For myself, listening to the matches by radio became a strong memory, as the broadcasts were often interrupted by reports from the capitals of Europe accompanying the Nazi invasion of Poland. Amid the horror of what probably lay ahead, probably only to this pre-teenaged sports fanatic did it greatly matter when the Aussies captured the Cup on the third day. Most tennis careers were distorted amid the six years of war that followed. Joe Hunt would graduate from the Naval Academy and later lose his life in naval aviation. Kramer would spend the war years in the U.S. Coast Guard, including landing-ship duty in the Pacific. In postwar 1946 Jack, now 24 and still competing as an amateur, won the U.S. Nationals singles and in December joined Californian Ted Schroeder in Melbourne in regaining the Davis Cup from the Australians. The two Americans won both first-day's singles and then combined to capture the doubles. In the next year, 1947, Kramer won both Wimbledon and the U.S. Nationals, and he and Schroeder again beat the Australians in the Cup final. Among those attending the Cup matches at Forest Hills was this writer, then 19, home on summer leave from the Naval Academy. There had been no tv-tennis in those days, and I remember being mildly surprised on seeing the slender physique of Big Jake. Kramer became widely regarded as an early practitioner, indeed the initiator, of all-out serve-and-volley tennis. But Jack pointed out that this reputation was inaccurate, as his ground game was also very strong. The net-attacking label grew during his pro career, which began on December 26, 1947, in Madison Square Garden amid a blizzard outside. Jack's opponent was Bobby Riggs -- the acknowledged postwar pro champion, who had edged out Budge in the pro wars of 1946 and 1947. Both Riggs and Kramer wrote how upon turning pro, each found that the net was the best place to be in indoor fast-court tennis. Riggs, who was small in stature and was seen as primarily a back-court player with excellent defensive skills, learned that lesson in contending with the likes of big hitters Budge and Frank Kovacs. In the Garden opener between Riggs and Kramer, Bobby was the comfortable winner amid a flood of Kramer errors against Riggs's excellent lobbing and net attacking. (Jack, however, led in placements 68 to 22.) Thereafter as the tour unfolded, for Kramer it became "kill or be killed" -- i.e., relentless and forceful net attacking behind strong approaches, coming forward behind serve, short ball, or return of second serve, always against Bobby's weaker, backhand side. The tally of tour wins was exactly even after 28 matches, but after that Kramer took command over the physically weakening Riggs, finishing ahead by 69-20. Like Vines and Budge before, the recent amateur champion (Kramer) had became the new king of the pros by beating the reigning pro champ. Jack would hold that distinction for six years. Kramer's next tour opponent would be Richard Gonzales, who had captured U.S. Nationals in 1948 at age 19 and repeated in 1949. The Gonzales-Kramer tour opened at the Garden in October 1949 with Riggs now the tour promoter-manager. Jack won in four sets and indeed won 21 of their next 25 engagements. Gonzales improved thereafter but finished behind, 97-26 in the final tally. Kramer wrote that Big Pancho, who would himself become the pro kingpin several years later, had been unprepared in 1949 both psychologically and in his tennis abilities for the demands of the pro tour. His bad neck helped by cortisone, Kramer in 1951 toured against Little Pancho -- Francisco Segura -- an attractive and underrated player who was familiar to pro audiences from the warm-up singles. Segura won the Garden opener but Jack captured the tour, 64-28. Crowds were small, as the box office seemed to demand a fresh challenger from the amateurs. That came in the person of Frank Sedgman, a superbly quick Aussie who had captured Forest Hills twice and Wimbledon once, meanwhile compiling an undefeated singles and doubles record in beating the U.S. in three Davis Cup finals. The 1953 tour became a Kramer-Sedgman match-up promoted by Kramer himself upon Riggs's exit from that role. On the court, Kramer, now in his thirties, was hard pressed by the challenger, who was then at prime tennis age 25. The Australian would win the U.S. opener in Los Angeles but Kramer finished ahead, 54-41. Sedgman was troubled by flu-like illness and a sore shoulder, Kramer with hip/back trouble. Jack wrote that the difference was Jack's second serve. It would be Kramer's last endeavor as a headliner on the main tour, completing his era as world pro champion, 1948-1953. That he was the world's best throughout that period, pro or amateur, is beyond question. Before that he was tops among the postwar amateurs, 1946-1947. PROMOTER The frustrations in organizing and managing the tour with Sedgman warned of more ahead as Kramer now became full-time promoter. For the 1954 tour, Richard Gonzales returned to main-tour action, joining Sedgman, Segura, and Budge, all under contract with Jack Kramer. Gonzales won the most matches in the round-robin scheme, but even at the Garden, the show proved a box-office flop. Kramer wrote that perhaps he should have kept himself in harness. Possible new recruits emerged, namely the whiz kids Lew Hoad and Ken Rosewall, who as teenagers had miraculously kept the Cup in Australia in 1953 and then reclaimed it in 1955 and 1956. Indeed, this new tennis generation, which included the American Tony Trabert, would stiffen pro tennis for the next decade and more. For promoter Kramer, however, the tribulations of the back-and-forth dealings with the principals worsened, especially with an ever-unhappy Richard Gonzales and amid the hostility of the Australian tennis authorities and press. Three great tours ensued, pitting Gonzales in turn against Trabert in 1956, Rosewall in 1957, and Hoad in 1958. All three tours were won by the acknowledged world champ since 1954, Pancho, though Hoad led for much of the 1958 tour before back trouble intervened. Kramer himself re-appeared in a world tour without Pancho in late 1957 where one objective was to prepare Hoad for the task of facing Pancho -- an approach that created another irritant for Gonzales. Hoad achieved a clear edge over Kramer during that exercise, but Jack beat Lew in the quarters of the prestigious Wembley tournament in London. That outcome argued for the integrity of the sport, as Kramer had a competing interest in building his newest recruit's reputation prior to the coming Gonzales tour. Kramer's business enterprise was now growing, with offices or representatives in several world locations, and its knowledgeable tennis people operated pro seasons in Europe, America, and Australia. The antipathy from the amateur side grew only stronger, even as public interest faded in tennis of all kinds, worldwide. Kramer avowedly stood for "open" tennis -- i.e., opening the Slams to the pros -- and this goal only narrowly failed in the 1960 voting at International Tennis Foundation. In late 1962 an embittered Jack Kramer decided to depart from his pro tennis czardom. As he put it, having tried everything he could, he would now remove himself as target of so much bitterness. There was, too, the reality that the tour had begun to produce losses for Jake, as the newer Aussie recruits, Cooper and Anderson, proved too weak for the older pros and therefore weak at the box office as well. But in a way, it worked. With Kramer mostly gone, other leadership moved into pro tennis. The great Laver joined the pros and, after early losses to Rosewall and Hoad, became the new on-court king. In 1967 two groups emerged to compete in organizing pro tennis and seeking fresh blood from the amateur ranks. Thus the pros soon commanded their deepest-ever monopoly of the world's top talent. Jack Kramer had a hand in organizing the 1967 professional tournament at Wimbledon whose success convinced the All-England Club to take the Great Step in 1968. After that Kramer would help in bringing the pro stars to the early open events, and in 1972 he became the first Executive Director of Association of Tennis Professionals, ATP. That role drew him to became a prime organizer of the 1973 boycott of Wimbledon by most of the pros -- an episode generally seen as strengthening the power of ATP and its members toward the national federations. Meanwhile the now-rising popularity of tennis could be measured in the growing sales of the Kramer-autographed wood racket made by Wilson Sporting Goods Company, Chicago. Kramer became a target for devotees of women's tennis -- unfairly as he saw it, saying that he was only against losing money on women's tennis. That had happened in 1951 when Gussy Moran and Pauline Betz joined the Segura-Kramer tour, and his view thereafter persisted that equal prize money for women's tournaments was unjustified. (Pauline was a much better player than Gussy, spoiling any competitive interest. But it was Pauline not the more glamorous Gussy that Riggs and Kramer tried to squeeze out.) Jack's valued role as tv commentator largely ended when the Billie Jean King camp insisted he be removed prior to her famous match with Bobby Riggs. Jack continued to organize and direct annual pro tournaments in southern California. Meanwhile he stayed upbeat as to the future of the sport. If anything, the eventual success of open tennis exceeded even Kramer's hopes. He approved of the shift away from grass courts, but was wary of clay as replacement for grass at U.S. Open and its tune-up circuit, believing that clay led to defensive, uninteresting play. The future, he believed, lay with hard courts, and he strongly agreed with their adoption soon afterwards at the new U.S. National Tennis Center and at U.S. Open. He underestimated the long-term influence of the non-wood rackets and newer varieties of string, believing that the baseline game would not long prevail over net attacking. He also underestimated the coming extreme success of women's pro tennis. Kramer's efforts to break down ill feelings and encourage players to think in terms of the game's benefit continued. Until his final departure, Jack Kramer saw himself standing first of all for The Game -- and ways to make it and its people prosper.** --Ray Bowers Arlington, Virginia. U.S.A. *FOOTNOTE Quoted in John Sharnik, Remembrance of Games Past: On Tour with the Tennis Grand Masters, MacMillan, New York, 1986, p. 243. **FOOTNOTE Jack Kramer with Frank Deford, The Game: My 40 Years in Tennis, G. P. Putnam's Sons, New York, 1979. This classic tennis autobiography, prepared with the talented writer Frank Deford, is filled with the author's unvarnished thoughts including his seeming biases. After thirty years, the book remains a foremost source on the period, not only on Big Jake himself but also on the whole world of top players and organizers. I recently bought a used copy from Amazon.com Los Angeles Tennis Center - UCLA Photos by Cliff Kurtzman   Bob Kramer:  Pam Shriver, International Tennis Hall of Famer:  Barry MacKay, tennis legend, promoter, and television commentator:  Bill Dwyre, Los Angeles Times:  Bill Kellogg, president of the USTA Southern California Section:     Jim Curley, US Open Tournament Director:   Eddie Merrins, long-time leading PGA teaching professional, Bel Air C.C.:  Tracy Austin, International Tennis Hall of Famer:   Donald Dell, International Tennis Hall of Famer:  Vic Braden:  Charlie Pasarell, NCAA champion at UCLA, professional tennis player, National Junior Tennis League founder, and promoter:  Ron Kramer:

1995 - May 1998 | August 1998 - 2003 | 2004 - 2015

This column is copyrighted by Ray Bowers, all rights reserved.

Following interesting military and civilian careers, Ray became a regular

competitor in the senior divisions, reaching official rank of #1 in the 75

singles in the Mid-Atlantic Section for 2002. He was boys' tennis coach for four

years at Thomas Jefferson High School for Science and Technology, Virginia, where

the team three times reached the state Final Four. He was named Washington

Post All-Metropolitan Coach of the Year in 2003. He is now researching a history

of the early pro tennis wars, working mainly at U.S. Library of Congress. A

tentative chapter, which appeared on Tennis Server, won a second-place award

from U.S. Tennis Writers Association.

Questions and comments about these columns can be directed to Ray by using this form.

|

October 2022 Tennis Anyone: Patterns in Doubles by John Mills. September 2022 Tennis Anyone: Short Court by John Mills. |

You will join 13,000 other subscribers in receiving news of updates to the Tennis Server along with monthly tennis tips from tennis pro Tom Veneziano.

You will join 13,000 other subscribers in receiving news of updates to the Tennis Server along with monthly tennis tips from tennis pro Tom Veneziano.